come back, lee marvin...we miss you (pt 3)

During the period between the middle of the 1960s through the late 70s, American filmmakers found a voice they had never imagined possible. The old Hollywood studios had collapsed, taking with them the censorship of the Production Code, and producers, conceding that the “Big Movie” colossus was an extinct dinosaur whose corpse was stinking up the box-office (“Ryan’s Daughter”, “Hello Dolly”, “The Adventurers” anyone?), and realizing that no matter how much they tried, they could not turn back the hands of the clock and force the public to passively accept the kind of mediocre pap they had swallowed for decades, they handed the studio keys over to the directors; in effect, allowing the inmates the run of the asylum. Looking back, it boggles the mind to think that major studios released movies like “Seconds” (1965;Frankenheimer), “They Shoot Horses Don’t They?” (1969;Pollack) and “Johnny Got His Gun” (1971-written and directed by Dalton Trumbo, who had less than twenty years earlier been imprisoned and blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten). For one brief moment in time, American cinema would rise above the conformity and conservatism that had crippled it for decades, and produce interesting movies that would demand something dangerous from American audiences: adulthood. But scanning through this veritable renaissance of American filmmaking, the question lingers- where was Lee Marvin?

Much has been made about the new actors whose stars rose during this period (and then faded at its’ end), and certainly their more naturalistic, sensitive performances greatly defined the current style. Exceptionally talented young actors like Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight, Robert De Niro and Bruce Dern (and the less talented but even more successful Warren Beatty, Ryan O’Neal and Robert Redford) were the official faces of this new Hollywood, they were not the only actors reaping the creative harvest of a (comparatively) free motion picture industry. During the Free Hollywood period, actors who had toiled in character parts or seen their careers stall suddenly came into their own, enjoying the best work of their lives. Actors like William Holden, Robert Duvall, James Colburn, Ben Johnson and Warren Oates suddenly found an opportunity in these new movies to explore a depth of character their earlier roles could never have provided. Even Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood, while relative stars already, only really blossomed as serious actors once the movies had matured beyond simply exploiting their prettiness. It would be, for most of these actors named, a decade of their most important, accomplished work.

Which is not to say there weren’t some pretty serious casualties, older actors who simply could not find a place amongst these new and interesting films. Charles Bronson, Lee Van Cleef and Jack Palance would wallow miserably in the b-movie purgatory- Bronson in particular seems to have been engaged in a shame spiral of increasingly dreadful vehicles. More tragically, some formerly established stars just couldn’t find the right role to make the transition; who remembers (or cares to remember) the post golden age work of such great actors as Rod Steiger, Jack Warden or Glenn Ford? But this list didn’t have to include Lee Marvin: buried amongst the forgotten dross he starred in through out his final two decades are a few exceptional films, not enough to satisfy, but just enough to tease us with what might have been.

In 1968 Marvin reunited with John Boorman, to film the brilliant “Hell In The Pacific”. Even though the lousy title (suggesting an eastern front version of the 1962 classic “Hell Is For Heroes”) promises yet another of the tedious WW II movies Hollywood was still inflicting on the public; it wasn’t. There are no heroic scenes of battle, no great or noble deeds, just Lee Marvin stranded on an island with Japanese superstar Toshiro Mifune. It’s a strange form of therapy, watching these two interact; both were real-life WW II veterans (obviously, on opposing sides), and both, at their best, were the great scene stealing hams of their respective nation’s cinemas. Wisely, Boorman risks the alienation of the audience by having neither (unnamed) character speak a word of the other’s language; the standard in Hollywood movies would be to have one of them prove to be such a linguistic genius that he almost instantly develops a command of the other’s tongue (the tongue mastered, of course, being english). Aside from any greater sense of realism their failure to communicate may provide, more importantly, it has the benefit of giving the actors the opportunity to engage in the manic flailing both were the undisputed masters of. At one point, Marvin having bested Mifune and now being the captor, he tries to teach his bound prisoner how to play fetch. Marvin throws the stick, then runs and picks it up in his mouth, hoping to show Mifune the (humiliating) game he wants to play. Mifune just silently watches, rolling his eyes and mumbling about how insane the American is every time Marvin runs to the shore to retrieve the stick. Regrettably, the one thing that could have made this ham jamboree complete didn’t occur to the filmmakers; including the sinking of a German ship, washing ashore the sole survivor, Klaus Kinski. But even with this holy triptych of the masculine screen left unrealized, “Hell In The Pacific” still manages to be a sad, beautiful little film. Side note-if you watch it on DVD, not only can you choose to add subtitles to Mifune (in the theatrical version, there were none), but you can also watch the original, far superior ending. In one of the few instances of Hollywood trying to impose a downer ending, the producers deleted the final scene of the two on them, now dressed in the uniforms of their respective countries, eyeing each other as enemies then parting. In the theatrical version, a sudden and abrupt explosion is superimposed over a frozen exterior shot – a lame, desperate attempt to attract a more youthful (and anti-war) audience.

“Fuck scripts. You spend the first forty years of your life trying to get in this fucking business, and the next forty years trying to get out.”

Lee Marvin, from his infamous 1970 Esquire interview

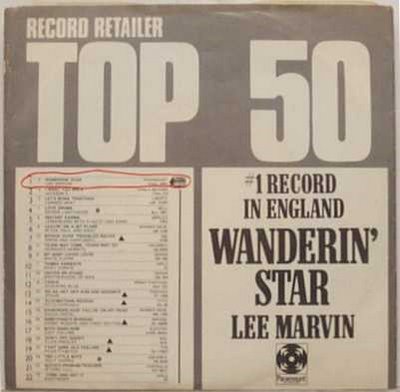

Marvin chose to follow-up the poetic beauty of “Hell In the Pacific” by costarring (with Clint Eastwood) in the three hour musical/western/comedy “Paint Your Wagon” (1969; Logan)- a choice that suggests the above quote may not have been made in jest. Listening to these two whisper/speak their way through songs like “Wand’rin Star” and “I Talk To The Trees” one can’t help but wonder who it was that thought there is an audience for this, that America was ready for singing and dancing cowboys? Reading the IMDb synopsis, I also can’t help but ask- considering how unenjoyable Lee Marvin’s bored mumbling and Clint Eastwood’s barely audible whispering is, just how bad a singer must poor Jean Seberg have been that they would have to dub her?

It’s difficult to pass judgement on Marvin’s later work, mainly because so little of it is available. Maybe the intriguingly titled “The Great Scout & Cathouse Thursday” (1976;Taylor) is an undiscovered classic (it does offer the only on screen pairing of Marvin and fellow alcoholic scene-stealer Oliver Reed); but until it’s released on DVD, it will remain undiscovered for those of us too young to have seen its’ theatrical run. Equally, I wouldn’t expect much from a movie called “Avalanche Express” (1979; Robson), but who knows? No one, at least until its’ reentered into general circulation.

What I do know is that, as uneven as his surviving 70s work may be, the unevenness is in the material, not Lee Marvin’s performances. For instance, “Emperor Of The North Pole” (1973; Aldrich) and “The Klansman” (1974; Young) were both built around ideas already dated by the mid-70s- both feel like movies that would have been far more important if they had been released ten years earlier. In “Emperor Of The North Pole”, A No. 1 (Marvin) is a veteran hobo, who reluctantly takes an obnoxious protégé (Keith Carradine) under his wing, and along for a ride on the forbidden train of evil conductor Shack (played with surprising fury by Ernest Borgnine). While the film was beautifully shot, and ends with an exciting fight sequence (on the moving train), the movie doesn’t bother to address why it is so important that the two hobos successfully bum a ride on this specific train- why the death of one person and the hideous disfigurement of an other is a reasonable price to pay just to earn the title “king of the road”. Perhaps if the original director slated for this project, Sam Peckinpah, had made the film, he probably would have developed the idea that A No. 1 and Shack are interchangeable, that they are both equally imprisoned by a type of egotistical masculinity that would rather face death than admit defeat. Under Peckinpah, the film might have even played with the generational difference between Marvin and Carradine – Marvin represents the modest, careful expertise of the WW II work ethic (even though a hobo, A No. 1 puts a considerable amount of work into the bumming of rides), whereas Carradine’s character Cigarette is a self-centered braggart who habitually lies through out the film to make himself seem more impressive than he is, and has the inflated sense of entitlement and disinterest in tradition and respect that largely defines the Baby Boomer generation. But Sam Peckinpah was lost in the booze and coke haze that would be his ultimate destruction, so in less subtle hands of Robert Aldrich, “Emperor Of The North Pole” never rises above the Hollywood simplicity of good versus evil, Villain ultimately defeated by Hero. The brilliant performances and beautiful cinematography deserved better than this. to be continued...

good lord!

good lord!Labels: classic movies, film, hollywood history, lee marvin, masculinity

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home