come back, lee marvin...we miss you (pt 5)

It’s not a coincidence that three of the five best American movies of the 1980s were projects begun in the 1970s ; it’s also not a coincidence that these three movies would be either mercilessly butchered or quickly shelved by Hollywood studios no longer interested in selling important movies to adults. “Once Upon A Time In America” (1983; Leone), “The Stunt Man” (1980; Rush) and “The Big Red One” (1980; Fuller) were all grossly mishandled works, and are all now seen universally as the few bright lights in the otherwise bleakest hours of American cinema(the other two are “Blue Velvet” (1986; Lynch) and “Paris, Texas” (1984; Wenders). What is particularly heart-breaking in the case of “The Big Red One” is that both its’ director and its’ star (Lee Marvin) would be long dead before critics and audiences discovered what the masterpiece they had made.

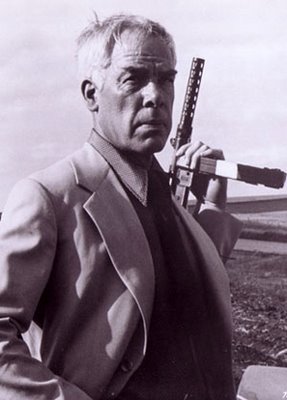

Legendary director Sam Fuller had almost worked with Lee Marvin once before, on the forgettable (and forgotten) 1974 film “The Klansman”. Fuller had written the screenplay and was slated to direct, when the studio suddenly got cold feet about the complexity of its’ ideas about race, and ordered a new script along the safe (and dated) lines of “Heat Of The Night” (1967; Jewison). Fuller quit in disgust, and Marvin tried to join him, but had already signed his contract. It retrospect, it was a good move on Marvin’s part to meet his contractual obligation, since he would continue to make movies, while Fuller did not get another chance to direct until “The Big Red One” six years later. As much as it might have been nice to have that earlier film been improved by Fuller’s direction, it could never have risen to the level that this movie does, could never have carved out such a vital place in the American canon.

Sam Fuller had written and directed World War Two films before this, just as Lee Marvin had acted in several, but neither would ever participate in a project as committed to telling the truth about the war both had fought in. “The Big Red One” is stripped of the grand heroism that mars most ‘classic’ war features, while rising above the sneering cynicism of Altman, Nichols or Kubrick. This film avoids both the glory and the folly of warfare, choosing instead to simply tell its’ reality. The great American essayist (and, like Marvin, a former Marine who fought in the Pacific) Gore Vidal once wrote that the feeling at the conclusion of WW II was not one of ecstatic victory, but rather of relief…that the newspaper headlines did not blare “We Won!”, like our male fantasies tell us, but rather “It’s Over”…a nation finally at the end of a long, dark journey it had no choice but to make. The four young soldiers in this movie (under the command of Marvin’s sergeant) don’t concern themselves with the “why” of their actions-they even admit that they barely even remember the “before” of their lives prior to the war. They wander through the nightmare of a ravaged continent, reduced to the acting and reacting that war requires. There are moments in this film that loan themselves to interpretation as “strange” or “surreal”… but are they really? The scene where they infiltrate an insane asylum seems bizarre, but later, after they’ve entered a concentration camp, the madness of the mental patients seems quaint. It is there that the formerly pacifistic Private Griff (a surprisingly good Mark Hamill) momentarily loses his sanity. Searching through the crematoria, he finds a German soldier hiding among the charred remains. The German’s gun malfunctions, and Griff shoots him…over and over again. Slowly, methodically, Griff pulls back the bolt on his rifle and fires another round into the (now dead) German. Hearing the steady rhythm of the rifle being fired and reloaded, the Sergeant investigates. He watches for a minute while his soldier continues bullet after bullet into the pulpy corpse. Griff had been “our” voice in the movie- the only one questioning the morality of killing and war…but now the horror has come home and he continues to fire until he runs out of ammunition. We expect his Sergeant to now move in, offering reassuring words to draw him back into sanity. Instead, he hands Griff another clip of bullets, then walks away. Sam Fuller’s war is a strange and interesting place, where the personal and moral priorities of those involved on all sides may not line up with what we expect (or want) them to. The soldiers can be fairly blasé about their fallen comrades, while angered by the difficulty of finding a prostitute who will fulfill the final wish of one of the dead soldiers (to hold her large, bare bottom against a cold window until it freezes). This isn’t the story Hollywood wanted to tell (the film would be horribly butchered before its’ release, with an added narration Fuller had not intended or liked). And sadly, it was the kind of story Americans didn’t want to be told.

At the same time, Hollywood studios were destroying the Weimar Republic that was ‘70s film, a former b-picture star was rising from the Right, declaring it the ominous-sounding “Morning In America”. Ronald Reagan, who spent the war fighting the good fight on studio soundstages, didn’t offer room in his new mythology for anything as unpleasant as doubt or honesty. Like all chicken-hawks, Reagan spoke passionately about the nobility of war, the eternal bravery of our fighting men in their sacrifice to our Blessed City On A Hill. This reverence for war (war ideally fought by others) cannot stomach any mention of brutality or wasted lives, or certainly questions about the validity of the cause. This Hero exists in a vacuum (and when played by Reagan, wearing a tailored uniform from the costume department), a vacuum defined and limited by the morality of a black and white universe. Hollywood was only too eager to adapt its’ product to match this moral absolutism, reducing all the stories it told to struggle (and inevitable victory) of superheroes over purely evil villains. Much has been made about the censorious Hayes office, and how its’ Production Code had crippled American cinema for decades. But much worse than its’ restriction of sexuality or violence, was the Production Code’s demand of cinematic justice; that all villains (or even just immoral characters) suffer their due fate by the end of the film. This restriction meant that, no matter what happens, and no matter how little it reflects real life, evil will always, always be defeated in the end by good. At the onset of the 1980s, Hollywood willingly chose to reshackle itself with this preposterous limitation, while still enjoying the post-Code freedom of foul language, swearing and tit shots. Remember, at the end of the first “Rocky” film (1976) he loses the fight, but wins the battle, since the victory is in the trying. In the subsequent four sequels, however, the only victory possible for the hero is complete and total annihilation of his opponent-an opponent who would become a greater caricature of evil with each successive movie.

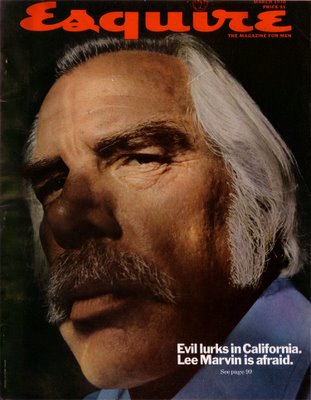

Once Hollywood had developed their new formula for making and marketing movies, a major problem quickly arose; since they were primarily making movies for children and adolescents (or adults with children’s minds), the old action stars simply would not do. Conveniently, death stepped in and helped clear the deck of a lot of the old leading men: in the matter of only a few years, many of the best of the old leading men would die. Steve McQueen, Warren Oates, William Holden, John Wayne, Robert Shaw, Burt Lancaster, Gig Young, John Cassevettes, Robert Ryan, Lee Van Cleef, Sterling Hayden, Slim Pickens and Henry Fonda would all die in a matter of a couple of years. Others didn’t die, but nor did they survive. Glenn Ford, Marlon Brando, Ben Johnson, Jason Robards, Paul Newman, James Colburn, Clu Gulager, Rod Stieger and Jack Warden opted for varying degrees of retirement, only appearing in films occasionally, and in small parts. Only James Colburn would eventually return to full time acting, enjoying a renewed popularity the final ten years of his life. Still others, because of mismanagement of money or because they simply couldn’t accept their obsolescence, continued working, in increasingly wretched parts. It’s heartbreaking to look at a chronological list of Charles Bronson’s or Telly Savalas’ work, and mutely witness the squandering of so much talent. There was a time once, I swear, when Ernest Borgnine wasn’t the shameless, over-acting hack that most viewers now remember him as. Aside from Clint Eastwood, who flourished during the 1980s, the only other Hollywood tough guy to survive the decade was Harry Dean Stanton- who became such a favorite actor of cult directors that some of his finest work sprung out of the barren soil of the 1980s.

So who did Hollywood replace the old tough guy actors with? Because they were now blatantly marketing movies to children (easier tie-in with breakfast cereal, toys and fast food restaurants), producers chose heroes that best fit the fantasies of young boys. As such, the screen hero of the 1980s is either a blank, indestructible killing machine like Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Chuck Norris or their endless army of clones (Jean-Claude Van Damme, Stephan Segal and Dolph Lundgren, to name a few). There’s a disturbing similarity between the expressionless face Stallone wears in the “Rambo” pictures, or Schwarzenegger maintains in the “Terminator” series, and the masked, silent butchers in the “Halloween” and “Friday the 13th” movies. The appeal of these stars, aside from their complete interchangeability, is that both the studio and viewer knows full well that they can barely speak,-let alone act- so there’s never the least threat of the performer wanting to branch out and experiment with roles more demanding than looking serious while the death toll mounts. The other type of male hero that blossomed out of this era, perhaps even more repellent that the Automaton Killer just mentioned, was the Arrested Adolescent in a Man’s Body. This type, while killing just freely and remorselessly as the other, isn’t a deadened slab of meat, but rather a hyperactive, preening child that jokes and mugs for the camera during the slaughter. Although reaching its’ zenith in the profound character studies Bruce Willis brought to the “Die Hard” movies, there are others subscribers to this screen style, all equally repellent. The appeal of Mel Gibson’s frantic arm-waving, eye-rolling screen persona always eluded me, until his recent arrest revealed that he is actually a master of autobiographical acting (“sugar-tits!!!”). His complete failure at understatement is particularly evident in the “Lethal Weapon” movies (note how many of these are plural- the sequel a sure sign of a movie aimed at the television-trained audience); it’s like watching a fourteen year-old act out his most perversely violent fantasies. Tom Cruise relies on this same childlike mania, augmented by his matching tiny magical sprite body. The performances these over-grown men bring to the screen are not heroic, they’re not even human…they’re live-action cartoons with a high kill ratio- Woody Woodpecker with a gun.

The studios did not want to offer, nor did the public wish to receive, images of everyday men fighting for survival. There was to be nothing ‘normal’, nothing human in the presentation of manhood. Gone were the world-weary faces of tough guys who smoked and drank too much. Instead, the screen would become the perverse mirror for vain, pretty men to admire their own beauty. As a people grow to hate themselves, they elevate the unobtainable to god-like status, morbidly wallowing in cheap fantasies offered by the ideal physique of a Stallone or Swayze. In this warpped ideology, where what makes a hero a hero (and ergo a man) is his cheek bones or pectorals, where manhood is measured by beauty and not accomplishment, the passive viewer (who is presumably not nearly as attractive as the slab of meat being showcased up on the screen) does not need to feel any regret or shame for their own weakness and failings. All that's expected of us is to sit back and enjoy the homoerotic ride. If the goal of the State and the Boss is to reduce us to helpless children, they could not find a better tool to convince us of our inadequacies than the motion picture heroes of the last quarter century.

There was no room for Lee Marvin in this new world of violent children’s movies, and so he died. It would take seven years for his body to join him- it was occupied with being dragged through five more films, all of them atrocious. It’s depressing to watch his corpse be dragged across the screen for the television sequel to “Dirty Dozen”, or it’s final violation, being used as a prop in a piece of Chuck Norris trash called “Delta Force”. But I have to remember, that’s not Lee Marvin, looking tired and regretful, interacting with his wig-wearing costar, it’s only his earthly remains. The real Lee Marvin died at the completion of “The Big Red One”, a movie that validated and legitimized his career.

At that movie’s end, the company having liberated the death camp, Lee Marvin finds a weak and dying young boy. He tries to feed the child, but he is too far gone to even chew. The Sergeant carries him out side, where they sit under a tree by a creek. After a while, he heads back to the camp. Either because he is so weak, or because they both crave some simple human contact, Marvin hoists the child onto his shoulders, carrying him around the compound. It is with this image that I choose to end the life and career of Lee Marvin.

the end

Labels: classic movies, hollywood history, lee marvin, masculinity