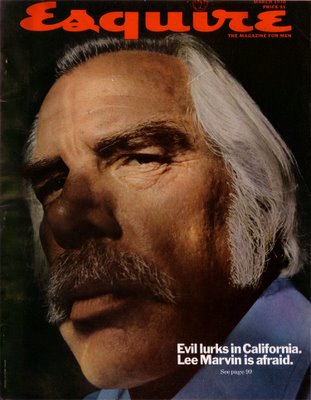

come back, lee marvin...we miss you (pt 1)

Lee Marvin could not have chosen a more fortuitous time to start a career in motion pictures than the early 1950s. Before the war, Hollywood movies were primarily built around female stars; it’s hard to maintain even a 3 to 1 ratio when compiling a list of 20’s and 30’s stars along gender lines. It was after the end of World War Two when the male star finally came in to his own; suddenly it was his name the marketing department exploited to promote a movie, his face across the posters and magazines. Part of the reason actresses suddenly found themselves, with few exceptions, marginalized in 1950’s Hollywood is a refection of the culture of repression and infantilization imposed upon the general female population that had experienced far too much freedom during the war, and needed a ‘retraining’ in subservience and domesticity; there is also the basic fact that the kind of movies being made in the post-war years simply didn’t need women. Rising from the silly Singing Cowboy fare it had been, the American Western found its’ language of mythology during that period, in large part through the work of John Ford. Westerns, along with war movies, rarely have choice parts for actresses, other than as damsels in distress-endangered virgins whose rescue provides a mettle proving opportunity for the hero. Even Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 “Paths Of Glory”, a subversion and condemnation of the romanticizing of war, is painted with an all-male cast, excluding the final scene, when a terrified German girl is forced to sing for her captors (it is, to be fair, the pivotal moment in the film-the only glimmer of beauty or humanity in an otherwise bleak and hopeless world).

During this same period the other cinematic celebration of masculinity, the crime drama, at its’ creative peak, and it was here that Lee Marvin made his first impression. Arriving from the New York stage, Marvin kicked around with bit parts on television and in now-forgotten movies (all westerns or war films), but it was as Vince Stone in Fritz Lang’s 1953 thriller “The Big Heat” that the public was formally introduced to his scene stealing talents. With surprising dexterity, Marvin manages to transform his considerable height from menacing sadist in one scene, to cringing coward in the next. In one of the most brutal acts of 1950’s cinema, he throws a pot of boiling coffee in his (loose-lipped) girlfriend’s face, hideously disfiguring her. Later, when she corners him with her own pot, he writhes and cowers, as loathsome in his weakness as he was earlier in his cruelty. While only a supporting role, this movie would be the beginning of Lee Marvin’s decade long apprenticeship.

So Lee Marvin served his apprenticeship, usually either as a villain’s henchman, hero’s buddy or as comedic relief. While these parts offered limited screen time, Marvin became a master of stealing scenes. Marlon Brando’s pouting mumble-mouthed Johnny in “The Wild One” has become a camp-culture icon; the homoerotic tight leather and teeny cap jauntily placed on his head as he sits on his motorcycle, fondling the trophy he’s strapped to his handlebars…the power of this image has long since surpassed the mediocrity of the film it appears in. But the reason the Brando image from “The Wild One” has become a household saint, while Marvin’s hasn’t, it’s because Lee Marvin is so utterly strange, so completely off the wall as Chino, that we lack the language to even define his performance. Looking like a post-apocalyptic pirate, Marvin literally throws himself across the screen, constantly falling to the ground or flying from one side of the screen to the other, his Chino, while trapped in the (confusing) sub-plot about the rival gang, explodes in manic delight every time the camera focuses on him.

His Meatball in “Caine Mutiny” (1954) was almost identical to his Chino a year before, but less noteworthy only because Humphrey Bogart (the father of all hard-livin’ tough guy actors) delivered the most bizarre character study of his career. Further supporting roles and television work followed, including “Bad Day At Black Rock” (1955) and as the quickly dispatched title character of John Ford’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1962). It wasn’t until 1964 that Lee Marvin was offered a lead role in a major motion picture, Don Siegel’s remake of “The Killers”. Remake is the key word here, because this film has always suffered in the shadow of the 1946 Robert Siodmak original (Criterion is so cruel as to package them as set, offering a poor contrast). But while the second version paled in comparison (not helped by the soon to retire from acting Ronald Reagan, who plays the villain with such obvious boredom and discomfort that it's difficult for the veiwer not to feel the same two emotions every time he's on screen), Lee Marvin shined all the brighter, earning a BAFTA for his performance. Even though Clu Gulager has almost as much screen time as Marvin (and John Cassevettes more), Lee Marvin is the star of this film, a deserved top-billing. And while another villain role (and the last of his career), Marvin uses this film to refine the image that would serve him through the peak years of his career. Gone was the frantic energy of his earlier films; his newly developed screen presence was economical in both movement and speech, a silver-haired panther silently waiting, ready to spring at any moment. Marvin's Charlie Strom watches impassively as Clu Gulager smacks first Claude Akins and later Angie Dickinson around. But it is when Marvin is finally rises and threatens them (going so far as to dangle Dickinson out a window) that they readily share their information. He moves through this movie like the Grim Reaper, slowly marching toward an inevitable armageddon. One of the great tradgedies of American film is that Lee Marvin never worked with director Sam Peckinpah; they both shared a belief that there is no such thing as a too elaborately choreographed death scene-the more ambitious the death, the more memorable the character. Having dispatched both Reagan and Dickinson, a fatally wounded Marvin staggers out of the house, flailing on the front doorstep. He stumbles several times, losing his gun but retaining the briefcase of money that had been his single obsession all along. When the police arrive, Marvin aims at them with his finger, 'firing' at them with his empty hand. He then all but flips backward, collapsing on the ground dead (like the blind children playing 'cops and robbers' in the opening scene). Although a flawed film, it is in "The Killers" that Lee Marvin matures into the weary, chainsaw-voiced wanderer locked into a specific purpose, neither understanding nor caring about the world beyond his fixation on the singular goal. It was a shift in persona that couldn’t have come at a better time.

Labels: classic movies, hollywood history, lee marvin, masculinity